I’m sure I made even the moss giggle on the velvety boulders left in the MacDowell woods, like the ones just outside Monday Music studio. There’s that gal running with a headlamp to the library again! And zoom—there she goes again, huffing and puffing on a bike this time, back up to Banks studio! But friends, it had been a whole decade since my last residency at MacDowell and I was unsure how to move in the dark or daylight by myself again, now a mama to two wily boys. Of course the incredible staff was sensitive to my every concern for safety and well-being. And because the book I was writing was about—and depended on!—me feeling safe again outside, I had to push my brown body to be alone outdoors, something I hadn’t really done in years. I had to not just tolerate the feel of forest light on my face, but I had to remember the girl I was who fearlessly splashed through creeks with jeans rolled up to my knees, lifting log and shale shelf in search of crawfish or tadpoles. I had to be willing to get lost with nothing but a trail map, bike, and water bottle.

*

My husband sent me a birdseed cake in a care package so I could hang it from the rear of Banks Studio and the same day I hung it up, a bluebird, cardinal, and a mourning dove came to see what it was all about. The wild turkeys kept their distance, but within the week, the seedcake was discovered by a squirrel pair who made off with it into the woods. The only thing left to visit me on the back porch was a dozen or so wasps. I wrote and wrote with the shadow of wasps across my face those weeks. I kept thinking it was confetti falling for a parade or celebration, but there would certainly be no parties until I turned in the essays to my editor, due at the end of my three-week stay.

*

One of the central questions I was trying to circle around (and then revise towards) during that time in the late summer of 2019 was Who gets to be outside and tell about it, and why? Why did I not ever find any books from Asian Americans who loved the outdoors? Why were publishers and fellowships not taking on these projects from Asian Americans? Why, when I was submitting my proposal around, did publishers and agents want me to include more sadness, more trauma, more death in my work? I had no plans to do so, but the assumption there was a market for Asian American trauma narratives, but none for joy and wonderment. And I know Asian Americans who are naturalists and who enjoyed the outdoors were out there, but my questions then became: why are they not being taught/published/included on reading lists and Best of the Year lists? Why is the gate closed as if it was still 1959, not 2019?

*

None of the plants or animals I loved observing in the MacDowell woods asked me the dreaded, “What Are You?” or asked, “Where Are You Really From?” Toni Morrison said something like, “If there's a book that you want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it.” But it’d be a mistake to think I was writing World of Wonders only for anyone who felt isolated from their communities. I’d like to think (dare I hope?) these essays are also for the people who were/are always part of the cool crowd, but who might’ve forgotten what it means to slow down and take in a bit of the outdoors too. I think I’m definitely not unique in terms of wanting to fit in and feeling a bit like a misfit during my teen years, but I think, and what I hope comes across is how much I found solace and comfort in studying and observing the natural world around me, how I couldn’t truly feel alone when there was such astonishing creatures and plants around me. And yet—as an avid reader, I never saw anyone who remotely looked like me featured in any of the books about the outdoors that I loved so very much.

*

First and foremost, I wanted to gather up a collection of plants and animals that made me fall in love a little bit with the outdoors, to celebrate the bounty and beauty (and darkness) of various wondrous plants and animals all with a lens of navigating time outdoors as an Asian American who loves to read and be outside, who watched her parents work so hard during the week but who always made a garden or hikes such places of comfort and safety. But I also realize with great sadness that feeling of comfort does not exist for everyone, especially many of my friends of color. There is so much that I don’t know about the natural world but I view that curiosity as a good thing, a place where I feel alive and my pulse quickens because I genuinely want to know the hows and the whys of creatures and plants with whom I share this planet.

*

I adore the poet Kwame Dawes, and I always come back to this quote of his: “We are political by our noise and by our silence.” What we choose to be excited about is political. For the longest time, I’d kind of cringe, thinking I’m not bold enough to be political. But his words really helped me own the power of my own enthusiasm. Think of how many things weren’t championed by the publishing world in the ’80s and ’90s. Think of how many things weren’t even encouraged to be written about. It’s not that there weren’t Asian Americans writing literature or writing about nature. The publishing houses chose not to publish them. That’s a political statement, too.

*

The whole time, even up until the day of my book’s publication this past September, I was like— really, who’s going to care about this brown gal who gets crazed with delight and excitement about the outdoors? And then BOOM—the pandemic happened and I just assumed the book would disappear. But people with vastly different experiences than me all over the world have said how much they’ve connected to this book. Or they felt seen. Or they felt like they could relax and unclench from the news a little bit, and they told their friend, and then they told their friend, etc. So to have it selected by Barnes & Noble as their 2020 Book of the Year, then spend eight weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list, is simply beyond my wildest imaginings. That’s not a humblebrag—I literally didn’t dream that was even possible for me.

*

I want World of Wonders to be like I’m sharing things I’ve been wanting to share with a friend, to open up the conversation and take us back to a time when we all were filled with wonder. When I flip through it now, I can remember those excited days at the end of one summer when I’d be hurrying through the woods at first because of my fear of being in such an isolated, quiet place, and then I can see my writing slow down and unfurl as those MacDowell trails and forest ferns helped put me at ease. Not to mention how the exquisite cooking staff kept my belly full, too. I finished World of Wonders with love in mind. I just hope it helps us to be a little more tender to living things we may not have seen or heard of before, to ourselves, and to each other— as we make our way through our own proverbial forests full of beasts and mossy rocks.

Get notified when the next essay is published

Find all Why MacDowell NOW? essays here

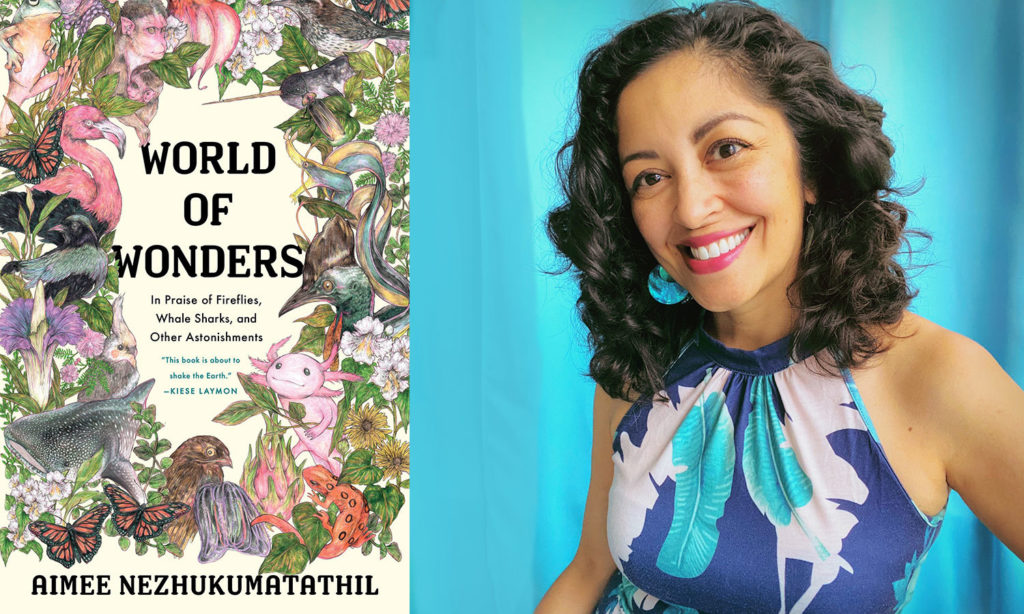

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is the author of four award-winning books of poetry, most recently, Oceanic (Copper Canyon Press), winner of the 2018 poetry award from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters. Her writing appears in The New York Times, Tin House, BuzzFeed, ESPN, and POETRY. Her illustrated nature essay collection, World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, & Other Astonishments, was released in 2020 from Milkweed Editions.