DeSantis’ Dearth of Understanding of America’s Past Fails Everyone in the Present

MacDowell Fellow, historian, and author Nell Painter. (Dwight Carter photo)

MacDowell Board Chair Nell Painter on art’s part to play in the fight against censorship.

By Nell Painter

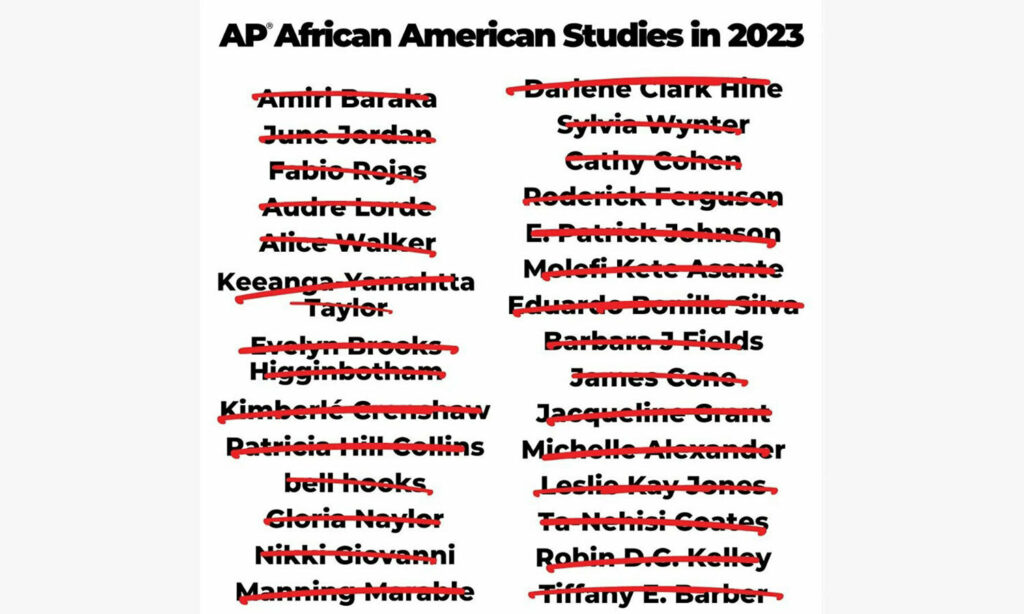

Here we are again, face to face with powerful attempts to push Black Americans – our experiences, our struggles, and our thoughts – out of the American consciousness. Let me borrow the words of a recent webinar from the African American Policy Forum featuring thinkers who have been excised from the College Board’s Black Studies AP course to supply a definition: “When Racial Reckoning and Anti-Wokeness Collide.” Professor Colette Gaiter listed these deleted thinkers in a recent Instagram post illustrating the College Board’s move.

These are thinkers who link thought to society, theory to praxis. They show the complexity and interrelatedness of identities and have a name for it: intersectionality. They envision a more just society through ideals exemplified by many artists and art organizations, including the nearly 100 MacDowell artists who are featured in our three “Conversation About Social Justice” web pages:

Conversation about social justice: Part 1

Conversation about social justice: Part 2

Conversation about social justice: Part 3

Much of the work featured in those pages, such as that from Mark Thomas Gibson (17), Annette Lawrence (18), Elise Engler (03, 17), Kristine Aono (90), Kevin Norton (02), and many others, refer directly to the time we are living through now. This MacDowell Fellows’ social justice art project grew from a need to speak out after a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, but that historical moment might have come at practically any point in U.S. history. Sadly and appallingly familiar, we’re mired in a cycle of anti-Black police brutality – anguish – anger – protest – White backlash. Decade after decade, police-murder of Black people. Decade after decade, White backlash against protest – a cycle documented in the books many leaders wish to expunge from our children’s education.

This time the White backlash comes from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in a campaign against Black Studies, dismissing the discipline as “significantly lack[ing] educational value,” as though it were something that just came up. A particular target this time, objected to by name, was the Black Panther Party. The objection didn’t refer to the heroes of Wakanda. Let me take you back to the 20th century, back to the 1960s, when protest gave birth to Black Studies. I remember the Black Panther Party, just as I remember when Black Studies emerged nationally in the late 1960s, from a protest movement of students who sometimes carried guns. The most widely known Black gun-bearers of the 1960s belonged to the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in my own hometown of Oakland. Half a century after the FBI’s COINTELPRO and internecine strife killed them off, the Panthers are still eliciting the Florida governor’s anxiety and demagoguery. It’s worth asking about the Panthers’ dangerous ideas. What were they? What did the Panthers stand for? They issued this Ten-Point Program in 1966:

- We Want Freedom. We Want Power to Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community.

- We Want Full Employment for Our People.

- We Want An End to the Robbery By the Capitalists of Our Black Community.

- We Want Decent Housing Fit For The Shelter of Human Beings.

- We Want Education for Our People That Exposes The True Nature Of This Decadent American Society. We Want Education That Teaches Us Our True History And Our Role in the Present-Day Society.

- We Want All Black Men To Be Exempt From Military Service.

- We Want An Immediate End to Police Brutality and the Murder of Black People.

- We Want Freedom For All Black Men Held in Federal, State, County and City Prisons and Jails.

- We Want All Black People When Brought to Trial To Be Tried In Court By A Jury Of Their Peer Group Or People From Their Black Communities, As Defined By the Constitution of the United States.

- We Want Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice And Peace.

These points elicited countless lively and curiosity-inducing discussions in the history classes I taught at American universities in my career. And for MacDowell artists and perhaps anyone interested in how art reflects and engages with culture and contemporary events, one of the startling legacies of the Black Panthers exists in their art. Emory Douglas, the BPP Minister of Culture, created an oeuvre of engaged art that belongs squarely in American art history. As I wrote in The New Yorker on June 18, 2020:

Right now, the art-history canon presents the nineteen-sixties as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, in images that depict an America without racial conflict and that celebrate consumer capitalism. Angry art inhabits a peculiar category of the art of protest, one peripheral to the history of American art. Let us recuperate the art that testifies to a long-standing, uncompromising opposition to police brutality. This furious art belongs not only to anti-racist heritage but also in the center of American art.

Point 7 condemns police brutality, a condemnation still needing to be heard. Point 5 envisions an activist Black Studies. In Oakland, Panthers demanded Black Studies in 1966. At San Francisco State University two years later, the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front staged the strike that created the school’s Black Studies department, and students in institutions around the U.S. followed suit.

You can read about and/or support the “Call to the College Board to Restore the Integrity of the AP African American Studies Course” here.

And if recent history is a guide, the assault on critical and social justice thinking won’t end with Black Studies. I fear other ethnic studies and Women’s and Gender Studies are next in line for attack.

The backlash is here, but the struggle to be heard and seen will also continue. Art will play its part in this process, for art’s reach is not so easily censored. MacDowell artists, like all artists, remain part of this story.

Nell Painter (16, 19, 21) is Madam Chairman of the MacDowell Board, Fellow, and a best-selling author.